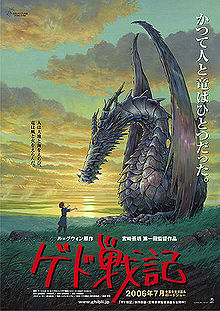

A few years ago, I found myself sitting in a movie theatre watching an animated adaptation of Ursula LeGuin’s landmark “Earthsea” series. Produced by the legendary Studio Ghibli, it marked the directorial debut of one Goro Miyazaki, son of the acclaimed animator and storyteller Hayao Miyazaki. I left the show feeling satisfied with the end result, and pondering where this new voice in filmmaking would go with his next piece, should he actually direct a second film.

A few years ago, I found myself sitting in a movie theatre watching an animated adaptation of Ursula LeGuin’s landmark “Earthsea” series. Produced by the legendary Studio Ghibli, it marked the directorial debut of one Goro Miyazaki, son of the acclaimed animator and storyteller Hayao Miyazaki. I left the show feeling satisfied with the end result, and pondering where this new voice in filmmaking would go with his next piece, should he actually direct a second film.

Earthsea ended up receiving a lot of heat from the animation community, panned for weak storytelling, unfinished ideas and a rushed “feeling” to the entire project. For my part, I saw the film as an emulation of what Ghibli had produced before: it definitely lacked the sense of identity and “personal voice” that classics like “Princess Mononoke,” “Spirited Away,” and “Pom Poko” had utilized to great effect, and at times felt like it was “trying too hard” to be a Ghibli film. Rather than create its own space, it was too preoccupied with fitting a specific mold that its predecessors had established.

Much of that blame was laid squarely on the shoulders of the younger Miyazaki. It’s no big secret that his father did not want him making that film. It’s no big secret that the elder Miyazaki had once tried to do the same, but was met with roadblocks from author LeGuin. It’s also no big secret that Goro’s insistence that he make the film translated to tensions between father and son. And it’s also no big secret that Earthsea itself is one of those “impossible projects:” literary works that are downright incompatible with translation to the screen (if you don’t believe me, feel free to watch the SyFy original movie adaptation of Earthsea…or just watch a film version of anything by Alan Moore).

I mention this because over the weekend I was fortunate enough to attend to US premiere of Goro Miyazaki’s latest film, “From Up on Poppy Hill,” a project he worked on in conjunction with his father as a sort of animated “olive branch” between two strained family members. And the first thought to run through my mind after the credits rolled was: “see, he can make a great film with the right source material.”

For starters, this film, which was adapted from the comic “Kokuriko-zaka Kara” by Chizuru Takahashi and Tetsuro Sayama, returns to a time period that Ghibli has had great success with in the past: postwar Japan. Set against a backdrop of the looming 1964 Olympic games, 16 year old Umi Matsuzaki must come to terms with both the loss of her father years earlier, and the emotions in her own heart as she builds a friendship with fellow student Shun Kazama.

This type of story is one that Ghibli has done time and again, from Laputa in the 1980s to 1995‘s Whisper of the Heart: strong themes of love, loss, nostalgia and reconciling the past and present in a time of great change pervade every line and scene, introducing westerners to many of subtle (and often unrecorded) path of “progress” Japan has been on since the mid-1800s. Conflict between heritage, history and embracing the future has been a frequent one, and finding that balance between the two is both challenging and rewarding- in many ways, this film is a sort of “collective version” of the under-known “Only Yesterday,” a similar tale with a similar outcome, and similarly satisfying in its resolution.

This type of story is one that Ghibli has done time and again, from Laputa in the 1980s to 1995‘s Whisper of the Heart: strong themes of love, loss, nostalgia and reconciling the past and present in a time of great change pervade every line and scene, introducing westerners to many of subtle (and often unrecorded) path of “progress” Japan has been on since the mid-1800s. Conflict between heritage, history and embracing the future has been a frequent one, and finding that balance between the two is both challenging and rewarding- in many ways, this film is a sort of “collective version” of the under-known “Only Yesterday,” a similar tale with a similar outcome, and similarly satisfying in its resolution.

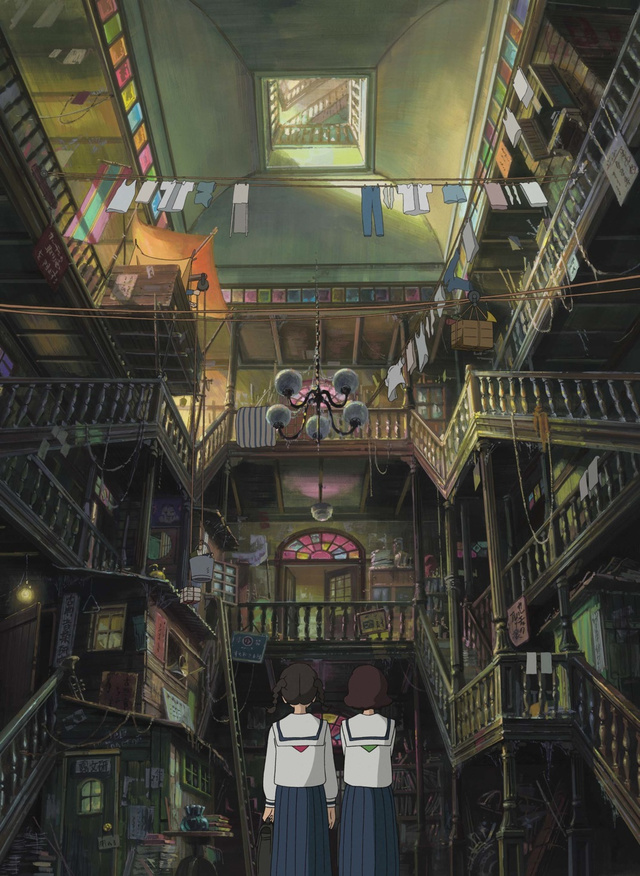

As the film progresses (and quite humorously, at that), Umi and Shun becomes leaders in a “cleanup” for their school’s historic “Latin Quarter:” a clubhouse that has fallen into disrepair and is in danger of being torn down to make room for “progress” in the form of a new facility building. As their efforts gradually build, more of their fellow students join in the cause, transforming the repair work into a near school-wide project that serves, as Umi states, to bring them together as a community. More than just a home for the “misfit” clubs, the building symbolizes that intangible connection that runs through all students in the school, and while some might be apathetic to the loss, it simply makes those dedicated to the project work that much harder.

At the same time, Umi is struggling to come to terms with both her lost father, her feelings for Shun, and a revelation that threatens to derail the friendship that has allowed for them to spearhead the Latin Quarter project. This part of the narrative is similar to many that Ghibli has done in the past, and might even be considered obvious for anyone who has watched the “canon” before. Though, in its defense, it is handled very well, and far more “organically” than earlier films like Whisper of the Heart. While the true joy of the film revolves around the Latin Quarter, neither plot feels overblown or underdeveloped, but rather balances and revolves well around each other (something which was lacking in films like Arrietty). You actually care about that old Latin Quarter building- partly because of its playful charm, and partly because of all the students and alumni who cherish the memories they made there. You feel hope for the young Umi, ever diligent in her raising of the signal flags, pointing a way home for her lost father. You laugh at the exaggerated mindsets of the club members, so enthralled by their studies, but still willing to come together for a collective goal that unifies and defines what they share, and are at risk to lose. You actually develop a stake in the entire affair, rather than simply watch a story unfold.

At the same time, Umi is struggling to come to terms with both her lost father, her feelings for Shun, and a revelation that threatens to derail the friendship that has allowed for them to spearhead the Latin Quarter project. This part of the narrative is similar to many that Ghibli has done in the past, and might even be considered obvious for anyone who has watched the “canon” before. Though, in its defense, it is handled very well, and far more “organically” than earlier films like Whisper of the Heart. While the true joy of the film revolves around the Latin Quarter, neither plot feels overblown or underdeveloped, but rather balances and revolves well around each other (something which was lacking in films like Arrietty). You actually care about that old Latin Quarter building- partly because of its playful charm, and partly because of all the students and alumni who cherish the memories they made there. You feel hope for the young Umi, ever diligent in her raising of the signal flags, pointing a way home for her lost father. You laugh at the exaggerated mindsets of the club members, so enthralled by their studies, but still willing to come together for a collective goal that unifies and defines what they share, and are at risk to lose. You actually develop a stake in the entire affair, rather than simply watch a story unfold.

Plot aside, this film is also absolutely lovely to watch: the “Ghibli aesthetic” is wonderfully present in lush colors, the variety of character/face designs and the use of shadow and subtlety to differentiate between cities and settings. Fresh is fresh, dingy is dingy, locations come alive of their own accord- all things that Ghibli has perfected over the years, and viewers have come to expect. While it lacks some of the “fantastic” elements found in the elder Miyazaki’s classics, it still manages to reflect and convey its own distinct form of “old world charm” in both the clubhouse and the surrounding port town. (In particular, that first glimpse inside the Latin Quarter is probably the most “Glibli-like” visual sequence in the film: some might wonder if they would get lost amidst the dust and gathered relics of clubs past.)

When I speak about the films of studio Ghibli, I often make mention that if Earthsea is the worst film Goro Miyazaki makes, it’s a pretty good start to his career. From Up on Poppy Hill is proof of that: his ambition is clearly present in the direction, while his father’s steady hand keeps him from running “off the page.” As a collaborative effort, this film is both solid and enjoyable. It’s not perfect, but much like the setting and story, neither are those who live in it, and that just adds to its charm.