I’m a strong advocate for the storytelling power of graphic novels. Not just books devoted to super-heroics or collections of assorted back-issues, but those timeless and classic stories that only visual media can seem to properly execute. From the subtle commentary of “Watchmen” and “Maus” to the elaborate fantasies of “Bone,” down the personal explorations of “Local” and “Blankets” before landing squarely inside the pure fun of “Hellboy” or all those volumes of “Fables” I have sitting on my shelf.

I’m a strong advocate for the storytelling power of graphic novels. Not just books devoted to super-heroics or collections of assorted back-issues, but those timeless and classic stories that only visual media can seem to properly execute. From the subtle commentary of “Watchmen” and “Maus” to the elaborate fantasies of “Bone,” down the personal explorations of “Local” and “Blankets” before landing squarely inside the pure fun of “Hellboy” or all those volumes of “Fables” I have sitting on my shelf.

But all that pales in comparison to the majesty and prevalence of the graphic novel within the scope of manga. Unlike American comics, we already are well-informed about the many genres and stories scuttling around the Japanese print medium. And many of these genres have introduced us to gems that at first might not even “feel” like an illustrated story.

Case in point: I just finished the fantastic “NonNonBa” by the incomparable manga-ka Mizuki Shigeru. For those unfamiliar with the name, Mizuki is one of modern Japan’s most respected creators of geki-ga, or manga written for adult males. A far cry from the weekly shounen action series or romantic shoujo, geki-ga manga often contains realistic stories, deep characterization and social commentary that we in the US would expect from novels written by a Tom Clancy or Nelson Demille. I wrote a review of one such title for my first ever article on this site back in 2010. But after finishing “NonNonBa,” I finally feel like I’ve taken a step into a much larger world.

Mizuki is known for two major contributions to the geki-ga stage: war stories, drawn from his own experiences during World War II fighting, and tales of ghostly youkai and other embodiments of the weird. In fact, Mizuki might be one of the foremost scholars on youkai theory currently in Japan, with his seminal works like “GeGeGe no Kitaro” and essays on exploring the hidden worlds of the supernatural. NonNonBa is something of a mix between these two very different types of stories: it’s an autobiographical look at his life growing up in pre-war Japan, and his introduction to those same monsters that would eventually populate his future works.

Much of the story is centered on the young “Gege” as he fights daily “wars” with neighboring boys, tries to navigate his schooling and watches as friends around him live and die. In addition there is a good deal of exploration into his own family structure, with a father who, despite being the only man in town to attend college, is content to be a simple bank teller and dream of opening a cinema; a terminally ill cousin who comes to live in the country before she passes; a mother descended from samurai nobility; and a brother torn between responsibility and personal desire. These characters revolve around a singular old woman known affectionately as NonNonBa, a former prayer woman who lives in poverty but manages to bring a touch of old-Japanese wisdom and grace to a slowly more chaotic world.

Much of the story is centered on the young “Gege” as he fights daily “wars” with neighboring boys, tries to navigate his schooling and watches as friends around him live and die. In addition there is a good deal of exploration into his own family structure, with a father who, despite being the only man in town to attend college, is content to be a simple bank teller and dream of opening a cinema; a terminally ill cousin who comes to live in the country before she passes; a mother descended from samurai nobility; and a brother torn between responsibility and personal desire. These characters revolve around a singular old woman known affectionately as NonNonBa, a former prayer woman who lives in poverty but manages to bring a touch of old-Japanese wisdom and grace to a slowly more chaotic world.

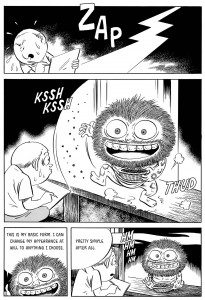

In addition to counsel, NonNonBa also provides young Gege with his first taste of the world outside his own, telling him stories of ghostly presences and lurking monsters who could appear in front of him at any time, whether for good or ill. Of course, Gege is drawn to these stories and begins to both devour them, and create his own, eventually utilizing them as an outlet for his own fears and frustrations. His interactions with one in particular, the Azuki Hakari (a bean-throwing goblin with a hairy face and sometimes sarcastic demeanor), set the tone for his future interactions with the weird, which play out alongside the occasionally sad events his life takes. Not as tragic as his war pieces, this story manages to blend hardship with the playfulness of youth, creating something that feels both authentic and rewarding to the reader.

Artistically, NonNonBa is unlike most manga available: not as many sharp edges or huge eyes, a very “realistic” character design that caricatures his friends and family, and lovely backgrounds that bring his small town to life. Not a lot of “action shots,” but plenty of facial expressions and diversity that relay emotion better than any amount of text could, which blend in well with the dialogue and general “mood” of the story. For readers unfamiliar with geki-ga as a whole, this book might come as a bit of a shock, but one that is easily overcome as the story comes “alive.”

As an introduction to both the genre and the works of Mizuki, this books shines as a readable, beautiful reflection on the life the young author led, and a powerful look into both his motivations and the world of pre-war Japan as a whole. Don’t let the lack of busty girls or powerful attacks detract from the splendid world Mizuki is offering a glimpse into- it will both inform and entertain the reader for the 400+ pages the story takes.