Last year, the anime world was introduced to a magical girl series by the name of Puella Magi Madoka Magica. Often cited as a refutation of previous mahou shoujo series, a deconstruction of moe/lolicon storytelling, and a turning point within anime on par with Neon Genesis Evangelion, the show reached a huge audience both inside and outside of Japan, garnering acclaim, respect and legions of dedicated fans.

Last year, the anime world was introduced to a magical girl series by the name of Puella Magi Madoka Magica. Often cited as a refutation of previous mahou shoujo series, a deconstruction of moe/lolicon storytelling, and a turning point within anime on par with Neon Genesis Evangelion, the show reached a huge audience both inside and outside of Japan, garnering acclaim, respect and legions of dedicated fans.

The series was the brainchild of one Gen Urobuchi, and like much of the reviews and accolades suggested, it was a new direction for magical girl series. Fast forward one year, and a new product created by the same Gen Urobuchi is airing on Fuji TV in Japan. But anyone expecting frilly dresses and kawaii shoujo lolis will be in for a rude awakening, because it is as far from Madoka as one could feasibly get.

Psycho Pass is equal parts character study, crime drama, and science fiction horror show. Blending together elements of modern police procedurals (“Criminal Minds” fans take note) and dystopian SF realities (ditto, “Matrix”-heads), Urobuchi and the rest of Production I.G. have managed to create the most revolting, “controversial,” but completely addictive, series of the Fall season.

In a future where the world is under constant surveillance by a near-omnipotent AI called the Sibyl system, ordinary citizens are at the mercy of their “hue-” a multi-colored “aura check” symbolized by the Psycho Pass, an all purpose identification and sanity-measurement system meant to monitor their “crime coefficient,” or the likelihood that they will commit a violent action. People who’s coefficient rises above a “normal” state, whether through criminal action or strong emotion, are at the mercy of police units composed of investigators and enforcers, whose job it remains to detain or execute those with unacceptable “criminal tendencies.”

In a future where the world is under constant surveillance by a near-omnipotent AI called the Sibyl system, ordinary citizens are at the mercy of their “hue-” a multi-colored “aura check” symbolized by the Psycho Pass, an all purpose identification and sanity-measurement system meant to monitor their “crime coefficient,” or the likelihood that they will commit a violent action. People who’s coefficient rises above a “normal” state, whether through criminal action or strong emotion, are at the mercy of police units composed of investigators and enforcers, whose job it remains to detain or execute those with unacceptable “criminal tendencies.”

Enter into this fray Akane Tsunemori, a young and “idealistic” inspector fresh off her exams, who entered the police force simply because her aptitude tests placed her at the top rungs of society. Believing she can enact real change, she is teamed up with veteran enforcer Shinya Kougami, a former inspector who lost his position- and his freedom- when his pursuit of a single case caused his psycho pass to indicate him as a threat. As Tsunemori struggles to understand the world she has chosen to jump into, Shinya continues his obsession towards a lost partner, and a shadowy force hiding just behind the surface of crimes he finds himself investigating.

Enter into this fray Akane Tsunemori, a young and “idealistic” inspector fresh off her exams, who entered the police force simply because her aptitude tests placed her at the top rungs of society. Believing she can enact real change, she is teamed up with veteran enforcer Shinya Kougami, a former inspector who lost his position- and his freedom- when his pursuit of a single case caused his psycho pass to indicate him as a threat. As Tsunemori struggles to understand the world she has chosen to jump into, Shinya continues his obsession towards a lost partner, and a shadowy force hiding just behind the surface of crimes he finds himself investigating.

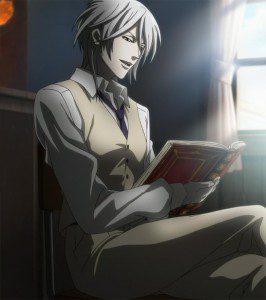

And lording over the crime and brutality that Akane and Kougami repeatedly find themselves surrounded by is one Shougo Makishima, a veritable “consulting criminal” on par with Moriarty himself. Not since Orihara Izaya has a villain come along content to just be a villain, and watch others carry out their schemes using his assistance. Meticulous, charismatic and savage in the extreme, Makishima plays his “allies” to their utmost, until their hubris (or mistakes) leads to their downfall, ultimately withdrawing his support and watching them be consumed by their building insanity.

One of the first striking aspects of this series is how dark it is. From rape in the pilot to murder, vivisection, retribution and internet anonymity, the show covers many of the same topics that are viewed as taboo or controversial within our own world. Not willing to shy away from the details, this is a series where bad things happen to ordinary people, often with no chance for last-second rescues or intervention by law abiding forces. It is common for story characters to disappear at the end of an episode, only to have their fates revealed in the following one. Trust is almost non-existent, as the enforcers themselves are often viewed as criminals who cannot be trusted (a fact that is explained in the first episode, when Akane is told her “Dominator,” the gun she uses to expediate action, can be fired at any enforcer at any time, and kill them), and inspectors can be seen as little more than “ticking time bombs,” just waiting for the stress of their job to take its “inevitable” toll.

As an exploration into the darker aspects of humanity, Psycho Pass is an excellent study of character: villains are not one-dimensional killing machines, but often multifaceted human characters, driven to crime through stress or the desire for “perfection.” Humanism, the idea that man alone represents the utmost perfection, is a powerful theme, whether exploring the motivations to kill or the motivations for justice. Watching a noble hero lose themselves to base instinct, or a drive bordering on obsession- normally a taboo subject itself- becomes part of the narrative, as characters come to the realization that the world is a dark, dark place, and one can only survive by accepting it, or ignoring it (and there are enforcers that do both).

Be forewarned, this series is not for the faint of heart. Like the aforementioned “Criminal Minds,” it is easy for a viewer to be repulsed by what they see. Urobuchi pulls no punches this time, and despite the show having elements of dystopian science fiction, the situations and actions of the characters are very much rooted in reality. There are scenes depicting violence against women, violence against teenagers, and bodily explosions on par with Gantz.

Be forewarned, this series is not for the faint of heart. Like the aforementioned “Criminal Minds,” it is easy for a viewer to be repulsed by what they see. Urobuchi pulls no punches this time, and despite the show having elements of dystopian science fiction, the situations and actions of the characters are very much rooted in reality. There are scenes depicting violence against women, violence against teenagers, and bodily explosions on par with Gantz.

But looking beyond the blood and depravity, you will find a deep, psycho-philosophical narrative about justice, hubris, duty and degeneration that will keep you hooked long after the credits role. Much like Madoka, this kind of show comes along rarely, and while I disdain using the term “required viewing,” Psycho Pass is one of those shows that anime fans should watch. It is a splendid depiction of character, atmosphere and storytelling that one would come to expect from Production IG, and especially Urobuchi. This series is easily the best one I’ve seen all year, and likely in years to come.

Watch Psycho Pass online at Funimation